|

Starting on June 16th, I will join a NYC non-profit to run their community science program. While I am sad to be leaving academia, I am excited for this new adventure and to move back to New York. As I make this transition, I'll share more in this space.

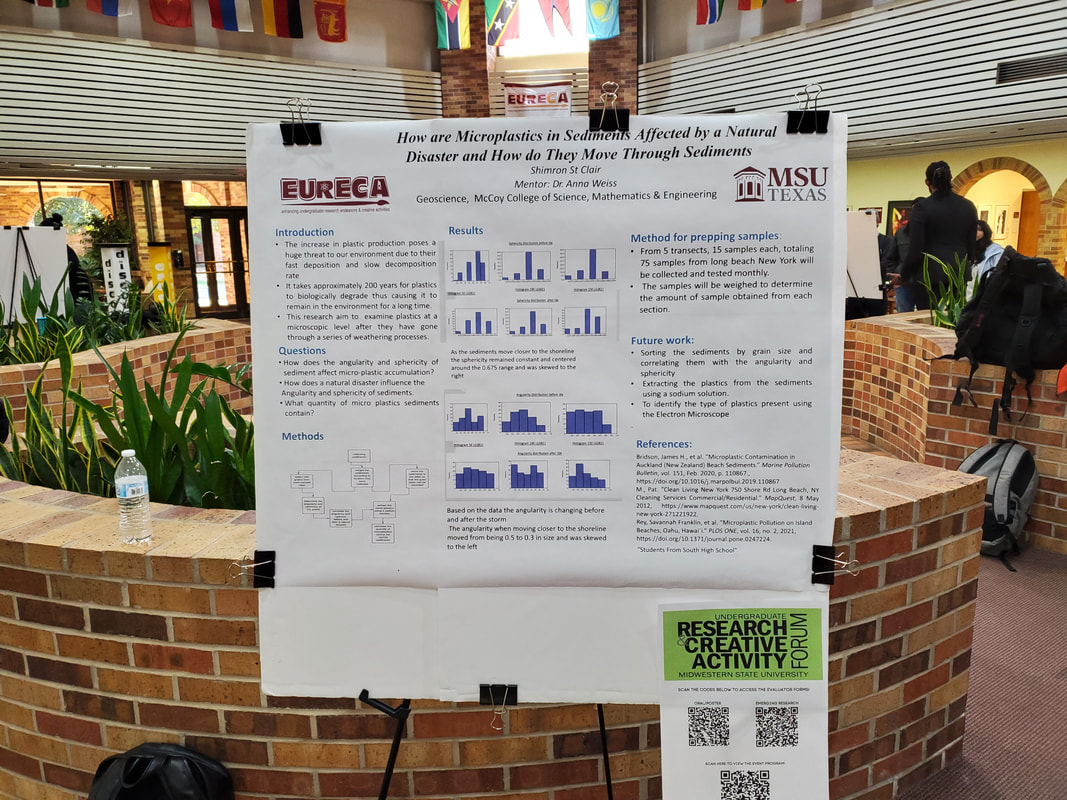

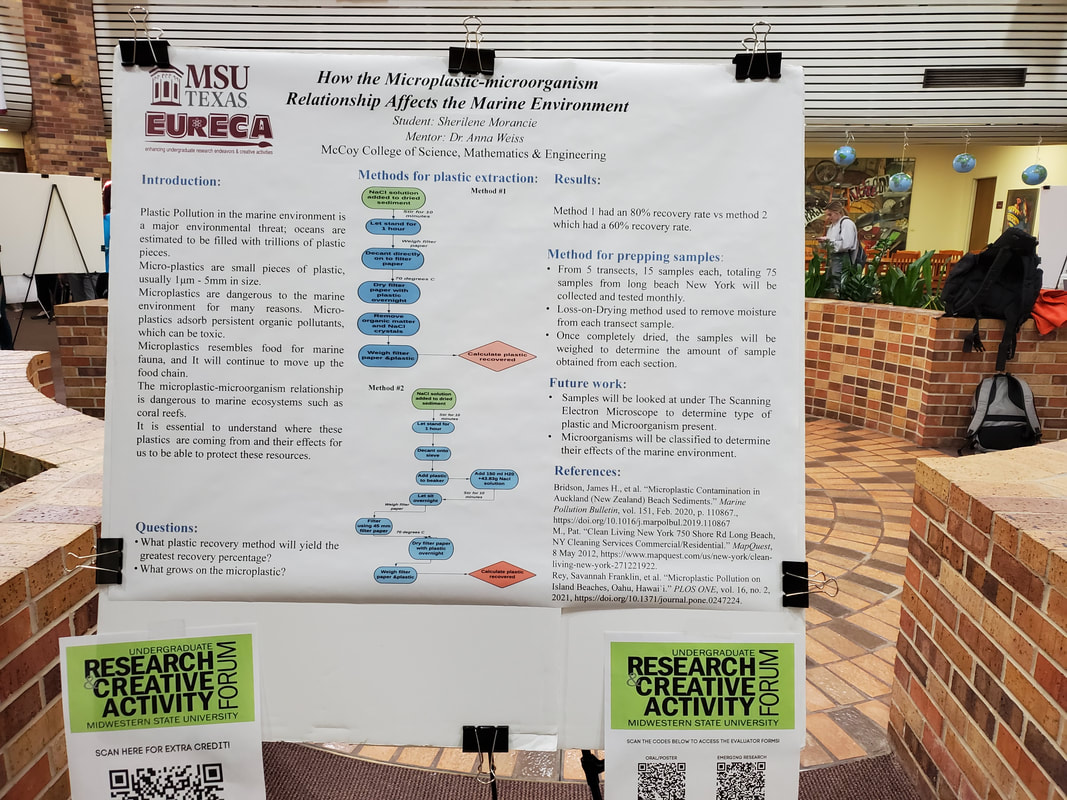

Paleoecology and Sedimentology at the MSU Undergraduate Research & Creative Activity Forum11/19/2021

Congrats to students Brandi, Shimron and Sherilene on great presentations at MSU's Undergraduate Research & Creative Activity Forum yesterday!

I had a great time at the MS&U Girls Conference talking to the next generation of female scientists about Marie Tharp and the sea floor. I used this fantastic bathymetry box activity from Jessica Kleiss at Lewis and Clark College:

https://nagt.org/nagt/teaching_resources/teachingmaterials/124130.html Below are pictures from the event (credit to Chelsee Kirk), as well as news coverage. I'm excited to announce that I am starting as an Assistant Professor in the Kimbell School of Geosciences at Midwestern State University in August. I can't wait to start my lab and teach about what I love! Go Mustangs!

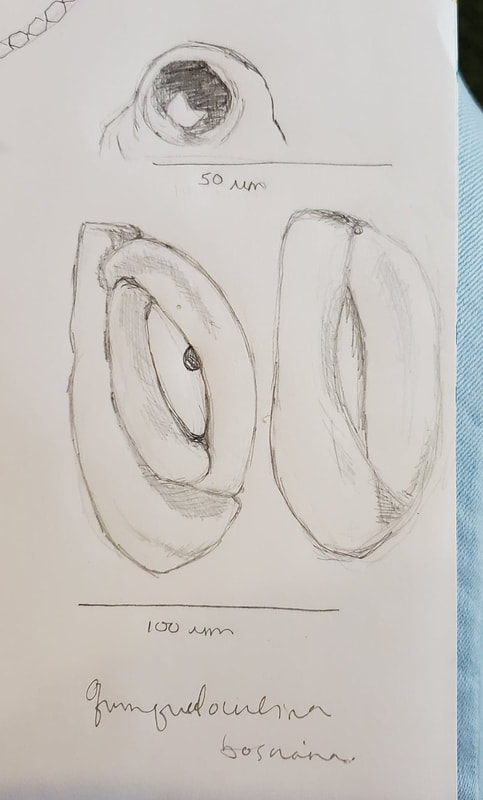

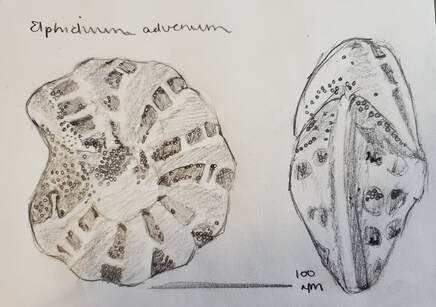

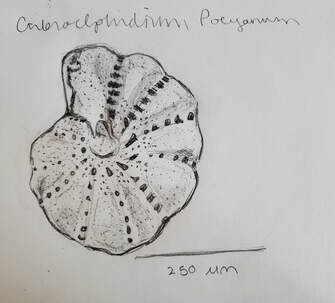

Since I can't work on my foraminifera sediment samples from home, I have been taking time to practice drawing them. Drawing samples always helps me see things in a way I hadn't before and helps me learn more about their anatomy. Here are some recent sketches (from photomicrographs) of forams from the region I currently work in.

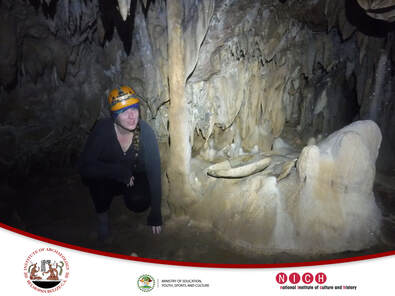

If the last few weeks of fieldwork have shown me anything, it's even when trying to minimize our impacts, humans can unintentionally cause a lot of damage to the environment. My B.Sc. thesis student Jimmy and I, along with several colleagues and assistants, have been assessing damage to several tourist caves in Belize. Below are images of our fieldwork, and some of the most common damages we saw. Images with the NICH and IA banner are taken by our collaborator and colleague, archaeologist Josue Ramos.

Above: Beautiful Cave Formations

Above: Getting around these caves can be a little dicey, to say the least

Above: My colleague's son, a budding geographer, helps me lay transect tape and make observations in the cave.

Above: Collecting data

Above: The most common damage we saw in the caves was: (upper and lower left) dirt, oil and abrasion from people touching cave walls and formations; (upper and lower middle) erosion from walking and hiking; (upper and lower right) broken artifacts and speleothems

Above, upper left: Jimmy tries to keep his notes dry as we cross the river. Above, right: It was tough but we survived!

My B.Sc. student Jimmy is studying the human impacts on karst environments, specifically caves, for his senior thesis. I've had the opportunity to assist him with his fieldwork, in collaboration with the National Institute of Cultural Heritage. The following photos are from a recent trip to study a cave in Western Belize that is not open to the public to compare with tourist caves.

Above: Jimmy and Josue, from NICH, laying transect tape inside of the cave.

Above: Cave entrance (L); Jimmy taking notes outside of the cave (R).

Top row: Cave formations; Bottom row: Stalactites (R); Bat skull found on the floor of the cave (L)

Top: Speleothems in the final cave chamber

Bottom row: Stalactites forming (L); Large speleothems (M); Going deeper into the cave (R)

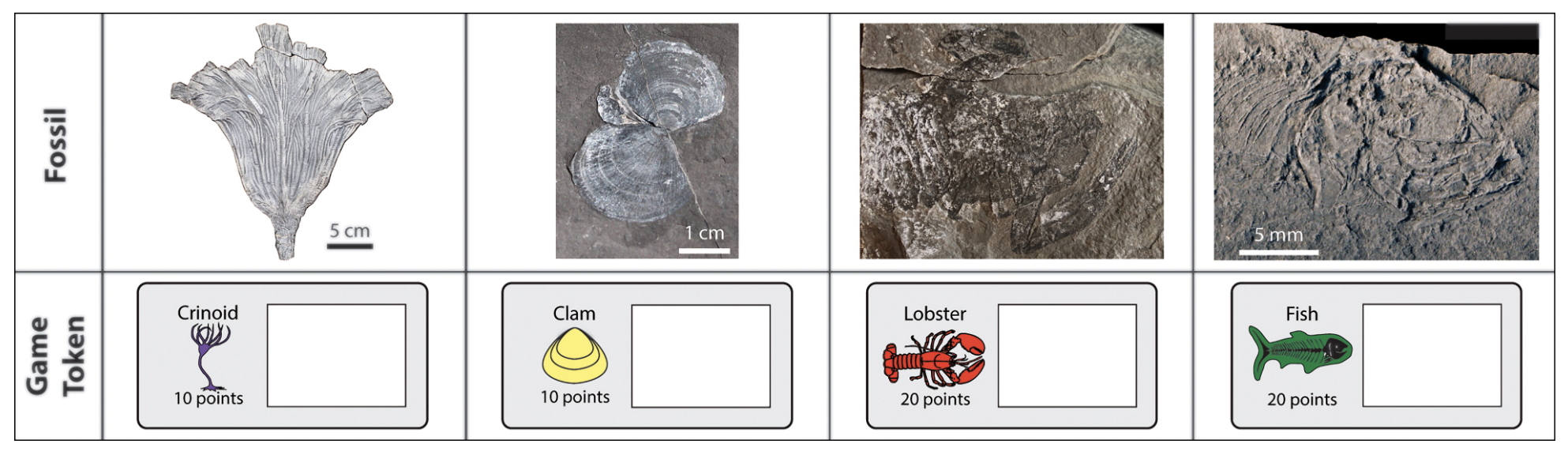

My new paper with Dr. Rowan Martindale introducing the Taphonomy Game and analyzing learning outcomes has been published (open access) in the Journal of Geoscience Education. Check it out here! The game pieces are also free to download and print to play in your classroom!

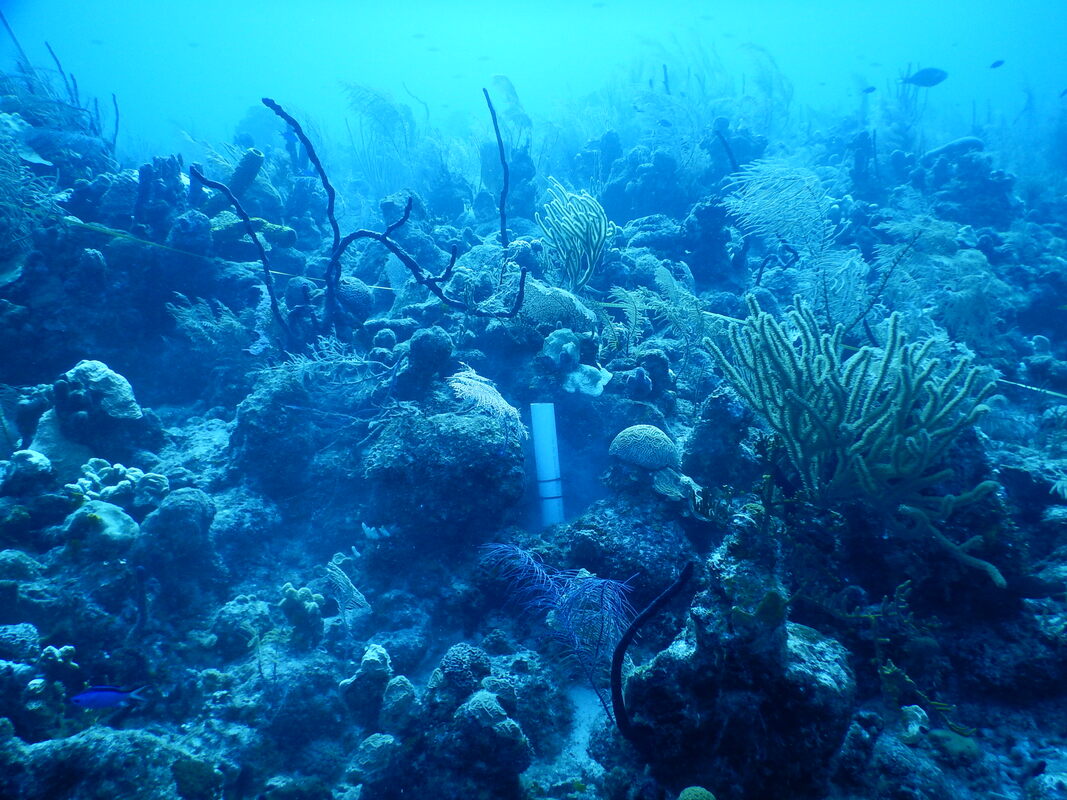

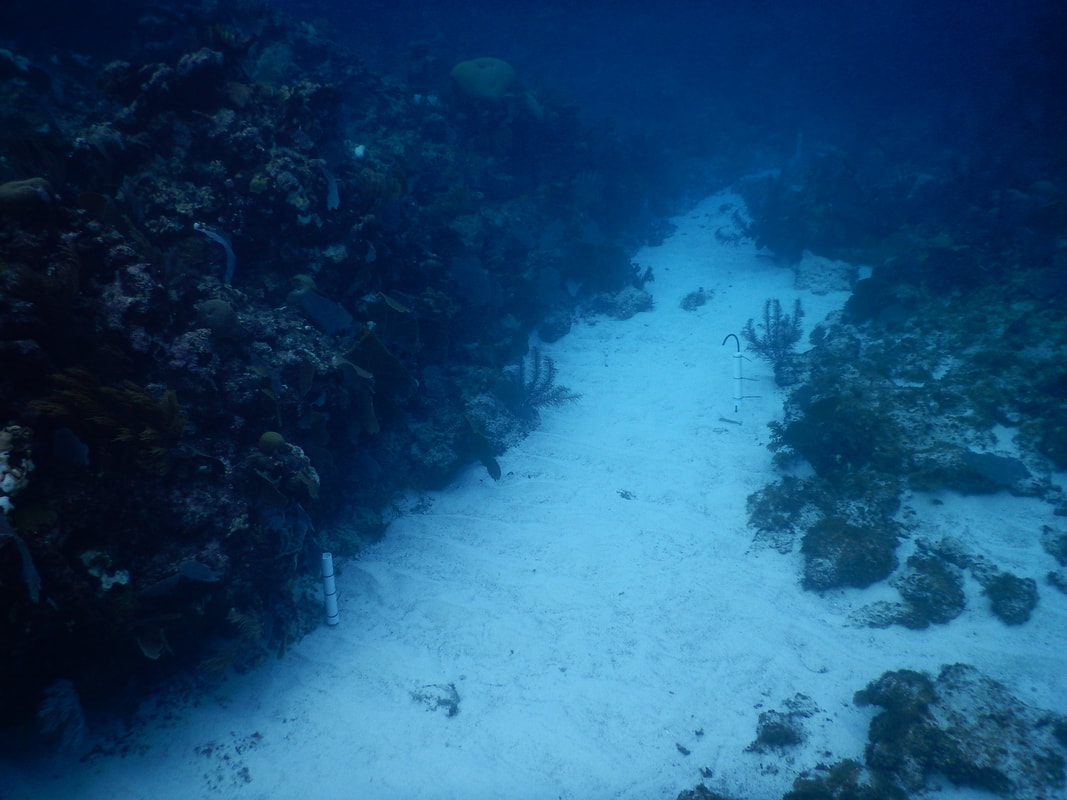

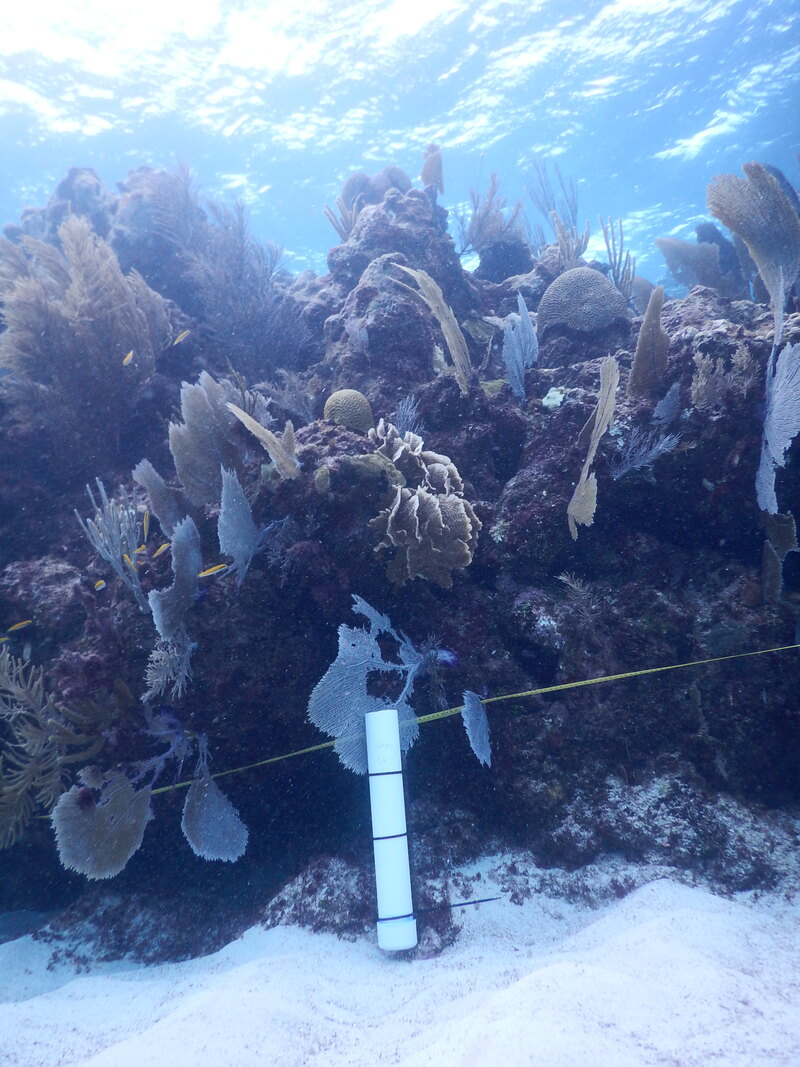

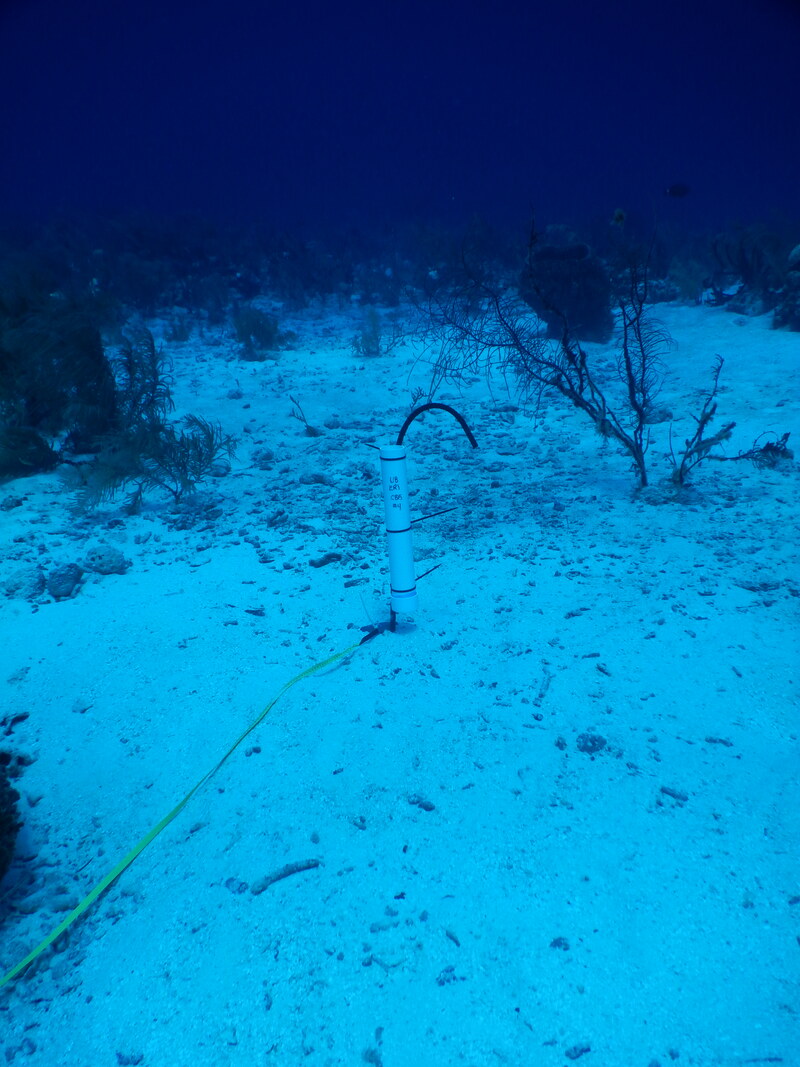

This week I am at Calabash Caye with my interns and students deploying sediment traps as part of our reef carbonate budgets project. Understanding how carbonate (the limestone rock made by corals and other reef organisms) is being produced, eroded and transported is important to assessing the overall health and structural integrity of the reef. Our sediment traps will tell us about the erosion and transport aspect of this equation. Keeping the reef structure strong is important because many animals, from fish to lobsters, make their home in the cavities of the reef framework. Having a strong reef also helps to protect the island from storms.

Above: Interns and I building sediment traps.

We have placed sediment traps in strategic places around the atoll to measure how much sediment is being carried into the system, how much is being brought out of the reef, and what is being re-incorporated into the framework. This long-term project will give us a holistic view of reef growth and health beyond the traditional measures of biodiversity.

Above: Students hammering rebar to keep traps in place

Above: Students and interns placing traps on reef.

Above: Finished traps in their place in the framework or open sand.

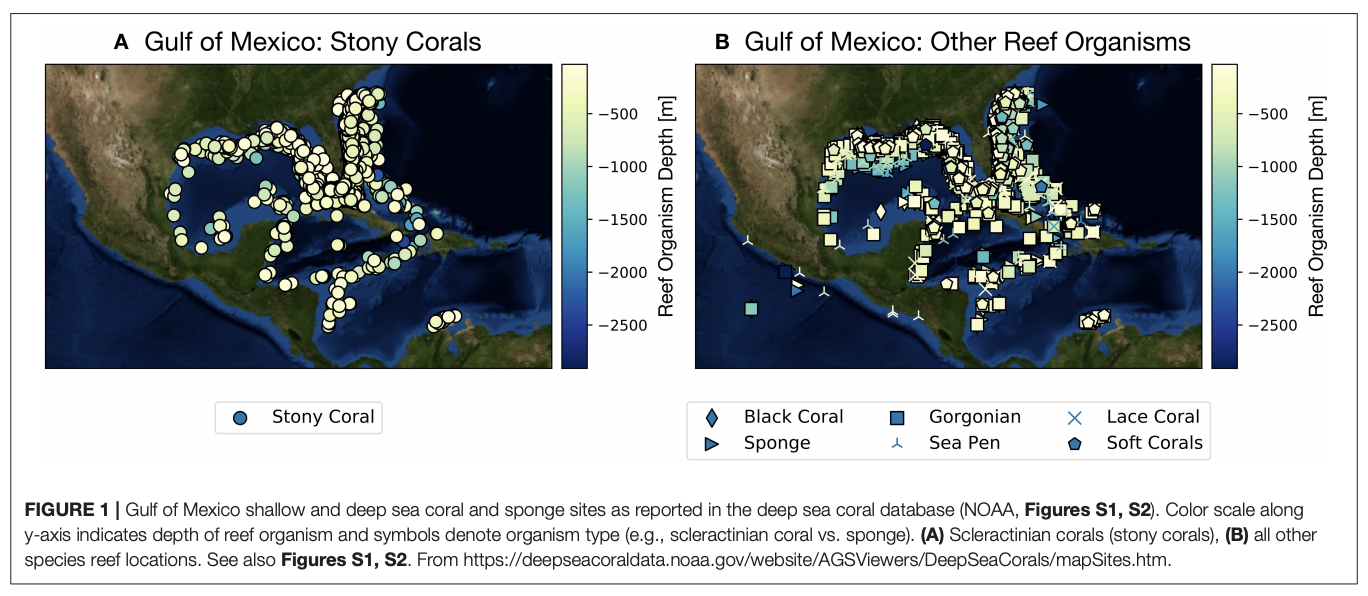

I had so much fun working on this paper with colleagues from UT Austin, Rice University and LSU. It's open access and available for download here: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2019.00691/full

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed